Frieze patterns, quantum information theory and group cohomology

In 2019, I successfully defended my Master’s thesis on matrix product states and symmetry-protected phases topological phases (see here). Now, almost 5 years later, I think it is the perfect time to write down a (short) introduction and overview of what I did during my thesis and how it relates to various fields of science.

This post is structured as follows:

- Short introduction to quantum mechanics.

- Why Matrix Product States?

- What is topological order?

- How is group cohomology involved?

- How to include spatial symmetries?

- Future perspectives

Whereas in classical physics, a physical system is completely characterized by specifying the position $\vec{x}\in\mathbb{R}^3$ and momentum $\vec{p}\in\mathbb{R}^3$ of all particles, a system in quantum mechanics is described by a state vector $|\psi\rangle\in\mathcal{H}$, where $\mathcal{H}$ is the vector space of all possible states. For example, the space of a two-state system such as the electron, which has an up state $|\uparrow\rangle$ and a down state $|\downarrow\rangle$, is given by the vector space $\mathbb{C}^2$.1

One of the main problems in quantum mechanics and quantum information theory is the so-called ‘curse of dimensionality’. When combining two systems in classical physics, we have to take the (Cartesian) product of the physical spaces, e.g. for two particles living in $\mathbb{R}^3$, the physical space is $\mathbb{R}^3\times\mathbb{R}^3\cong\mathbb{R}^6$. The dimension of the final space is simply the sum of the dimensions of the individual spaces. However, in quantum mechanics, individual state spaces are not combined through the Cartesian product, but through a tensor product (which preserves linearity). The dimension of the tensor product is equal to the product of the individual dimensions! For example, the state space of $n\in\mathbb{N}$ electrons is not equal to $\mathbb{R}^{2n}$, but to $\mathbb{R}^{2^n}$, i.e. the dimension scales exponentially in the number of particles. If we would try to work in this general space of state vectors, any algorithm would run out of memory.

However, an important result in quantum information theory was that most physically relevant2 states satisfy an ‘area law’. If we have a lattice system $M$ and we cut this system in two $(M=A\sqcup B)$, the bipartite entanglement entropy $S:=-\mathrm{tr}(\rho_A\ln\rho_A)$ only depends on the number of sites on the boundary $\partial A$. States satisfying this condition only occupy a very (exponentially) small subset of the total Hilbert space $\mathcal{H}$. In general, an efficient (low-rank) variational ansatz for solutions of such systems is given by tensor network states and, in one dimension in particular, the matrix product states.

A general system can be expessed as follows:

\[|\psi\rangle = \sum_{i_1,\ldots,i_n}C_{i_1\ldots i_n}|i_1\cdots i_n\rangle\,,\]where $\mathbf{C}$ is the coefficient tensor. This tensor can be recursively decomposed using the Schmidt decomposition to obtain an expression in terms of low(er)-rank tensors. At the first, where a bipartite cut is made between the first site and the rest of the system, the following expression is obtained:

\[|\psi\rangle = \sum_{i=1}^{d_1}\lambda_i[1]\,|\phi_i[1]\rangle\,|\Phi_i[2,\ldots,n]\rangle\,,\]where $d_i$ is the dimension of the local Hilbert space. By making a bipartite cut at every stage, the vectors $|\Phi_i[2,\ldots,n]\rangle$ can be expressed in terms of local bases. This leads to the following expression of the coefficient tensor:

\[C_{i_1\ldots i_n} = \sum_{\{i_k\}}^{\{d_k\}}\sum_{\{j_i\}}\Gamma_{j_1}^{i_1}[1]\lambda_{j_1}[1]\Gamma_{j_1,j_2}^{i_2}\lambda_{j_2}[2]\Gamma_{j_2,j_3}^{i_3}[3]\cdots\Gamma_{j_{n-1}}^{i_n}[n]\,,\]where the indices ${j_i}$, for $i\in\{1,\ldots,n\}$, run from 1 to $\min\left(\prod_{k=1}^i\dim(\mathcal{H}_k),\prod_{k=i+1}^n\dim(\mathcal{H}_k)\right)$. Finally, to obtain the MPS representation, we simply have to redefine the tensors:

- $A[1]:=\Gamma[1]$, and

- $A_{m,n}^{i_k}[k] := \lambda_m[k-1]\Gamma_{m,n}^{i_k}[k]$.

To actually reduce the complexity of the state, i.e. reduce the dimension of the solution space, we can leverage the Eckhart–Young theorem, which states that the singular value decomposition (the Schmidt decomposition is essentially a restatement) is the optimal decomposition of a matrix in terms of lower rank matrices, and only retain the $D_k$ largest singular values in $\lambda[k]$, effectively truncating the local Hilbert space. The final Hilbert space $\mathbb{A}_{\text{MPS}}$ then has dimension $\dim(\mathbb{A}_{\text{MPS}})=\sum_{i=1}^nD_{i-1}d_iD_i$.

Although the general space of MPSs certainly has its use, we will focus on an important subset.

Equivalently, $A$ is injective if the transfer operator $\mathbb{E}[A]:=\sum_{i=1}^dA^i\otimes\overline{A^i}$ has a unique maximal eigenvalue.

The property of injective MPSs that is mainly of relevance to us, is the following. The center of $M_D(\mathbb{C})$ consists only of the scalar multiples of the identity matrix. Hence, any matrix that commutes with all matrices $A^i$ is necessarily such a scalar matrix:

\[\forall i\in\{1,\ldots,d\}:[X,A^i]=0\implies \exists\lambda\in\mathbb{C}:X=\lambda\mathbb{1}_D\,.\]More generally, if $X$ satisfies $XA^j=e^{i\varphi}A^jX$ for all $j\in\{1,\ldots,d\}$, then $\varphi=0$ and $X=\lambda\mathbb{1}_D$ for some $\lambda\in\mathbb{C}$. This can be used to prove an essential theorem about MPSs.

Until recently, the main paradigm for understanding phases of matter was the Landau–Ginzburg paradigm. The central role here is played by the order parameter $\xi$. When the order parameter is nonzero, the state is said to be symmetry-broken (which corresponds to an ordered phase). In terms of group theory, where the Hamiltonian of the theory has a symmetry group $G$, the symmetry-broken phases, with residual symmetry group $H\leq G$, are classified by the coset space (or, if $H$ is a normal subgroup, the quotient group) $G/H$. Towards the end of the 20th century, phenomena were discovered that could not be described by this paradigm. Inequivalent systems with identical symmetries, transitions between systems with different types of broken symmetries (hence, requiring multiple order parameters), etc.

An important new concept that arose, is that of topological order, where the term topological refers to the notion of topology and, hence, that of continuity.

If the local quantum circuit is required to preserve a given symmetry group, the states are said to be in the same symmetry-protected topologically ordered phase. Nontrivial phases correspond to states that cannot be transformed by a local quantum circuit to a product state.

Before diving into the subject of group cohomology and its application to symmetry-protected phases, we first give a more general introduction to (co)homology theories. These constructions usually arise in the classification of mathematical objects and the study of obstructions to certain ‘lifts’.

Because the groups $A_n$ are Abelian, so are the image and kernel of the morphisms $d_n$. This allows us to define the quotient groups $$H^k(A^\bullet) := \frac{\ker(d_k)}{\mathrm{im}(d_{k-1})}\,.$$ These are the cohomology groups of $A^\bullet$.

For the case og group cohomology, we first have to fix a group $G$ and a $G$-module $A$, i.e. an Abelian group $A$ equipped with a group morphism $\lambda:G\rightarrow\mathrm{Aut}(A)$. Denote by $C^k(G;A)$ the Abelian group of (set-theoretic) functions $G^k\rightarrow A$. These are called the $k$-cochains. The coboundary operators $d_k$ are defined as follows:

\[\begin{aligned}d_kf(g_1, \ldots, g_k, g_{k+1}) = \lambda(g_1)&\cdot f(g_2, \ldots, g_{k+1})\nonumber\\ &+ \sum_{i=1}^k(-1)^if(g_1, \ldots, g_{i-1}g_i, \ldots, g_{k+1}) + (-1)^{k+1}f(g_1, \ldots, g_k)\,.\end{aligned}\]The kernel of $d_k$ is denoted by $Z^k(G;A)$ and is called the cocycle group. Likewise, the coboundary group $B^k(G;A)$ is defined as the image of $d-{k-1}$. As above, we can now define the cohomology groups of $G$ with coefficients in the $G$-module $A$ as

\[H^k(G;A) := \frac{Z^k(G;A)}{B^k(G;A)}\,.\]The above complex is also called the normalized standard resolution or normalized bar complex. The reason for the denominator ‘normalized’ is that every cocycle is cohomologous to a ‘normalized’ cocycle, i.e. for every class $[\omega]\in H^k(G;A)$, there exists a representative $\omega\in Z^k(G;A)$ such that

\[\omega(g_1,\ldots,g_k)=e\]as soon as one of the $g_i$’s is equal to the identity $e\in G$.

Before going to the application of group cohomology in the classification of symmetry-protected topological orders, we first cover some important results in group cohomology (and homological algebra in general).

Consider two groups $G,K$ that act, respectively, on $\mathbb{Z}$-free modules $A,B$, i.e. modules that admit a basis over the ring of integers $\mathbb{Z}$. The group cohomology of the direct product $G\times K$ with coefficients in $A\otimes_\mathbb{Z}B$ is related to the group cohomologies of $G$ and $K$ in the following way:

\[\begin{aligned}H^k(G\times K;A\otimes_\mathbb{Z}B) \cong \bigoplus_{p=0}^k&\left[H^p(G;A)\otimes_\mathbb{Z}H^{k-p}(K;B)\right]\\&\times\bigoplus_{p=0}^{k+1}\mathrm{Tor}(H^p(G;A),H^{k-p+1}(K;B))\,,\end{aligned}\]where the operator $\mathrm{Tor}$, which is called the torsion product, has the following properties (a formal definition of this product is not relevant at this point):

- $\mathrm{Tor}(A,B)=\mathrm{Tor}(B,A)$,

- $\mathrm{Tor}(\mathbb{Z},A)=0$,

- $\mathrm{Tor}(\mathbb{Z}_m,\mathbb{Z}_n)=\mathbb{Z}_{\gcd(m,n)}$,

- $\mathrm{Tor}(A\times B,M) = \mathrm{Tor}(A,M)\times\mathrm{Tor}(B,M)$, and

- $\mathrm{Tor}(A,M\times N) = \mathrm{Tor}(A,M)\times\mathrm{Tor}(A,N)$.

Now, let $G$ be a finite group and let $A=\mathbb{R},\mathbb{Z}$ or $\text{U}(1)$. These fit in a short exact sequence as follows:

\[0\longrightarrow\mathbb{Z}\overset{\iota}{\longrightarrow}\mathbb{R}\overset{\exp}{\longrightarrow}\text{U}(1)\longrightarrow 0\,,\]where $\iota:\mathbb{Z}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}$ is simply the inclusion $\mathbb{Z}\subset\mathbb{R}$ and $\exp:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\text{U}(1):r\mapsto\exp(i2\pi r)$ maps real numbers to elements of the unit circle in $\mathbb{C}$. Every such short exact sequence of modules induces a long exact sequence in group cohomology:

\[\cdots\longrightarrow H^k(G;\mathbb{Z})\longrightarrow H^k(G;\mathbb{R})\longrightarrow H^k(G;\text{U}(1))\longrightarrow H^{k+1}(G;\mathbb{Z})\longrightarrow\cdots\,.\]An interesting consequence is that, since $H^k(G;\mathbb{R})=0$ for all $k\in\mathbb{N}$, we obtain an isomorphism

\[H^k(G;\text{U}(1))\cong H^{k+1}(G;\mathbb{Z})\,.\]As noted in the introduction to quantum mechanics in the beginning of this post, the correct setting is not simply the Hilbert space $\mathcal{H}$ of quantum states, but rather its projectivization $\mathbb{P}(\mathcal{H})$. The reason for this curious fact is that quantum mechanics is completely insensitive to scalar transformations and phase factors, since all physical quantities are of the form

\[\frac{\langle \psi\mid\widehat{O}\mid\psi\rangle}{\langle\psi\mid\psi\rangle}\,,\]where $\widehat{O}$ is an observable on $\mathcal{H}$. Because quantum mechanics is completely $\text{U}(1)$-invariant, symmetries are not necessarily implemented unitarily. Wigner showed that the correct notion is that of projective representations, i.e. group (homo)morphisms $\rho:G\rightarrow\text{PGL}(\mathcal{H})$. Where usual representations $\varphi:G\rightarrow\text{GL}(\mathcal{H})$ are required to satisfy

\[\varphi(gh)=\varphi(g)\varphi(h)\,,\]projective representations only have to satisfy

\[\varphi(gh)=e^{i\omega(g,h)}\varphi(g)\varphi(h)\,.\]For translation-invariant systems, we can always choose an MPS representation in which the tensors at every site are identical (a uniform MPS).3 In such a case, it can be proven that symmetries are implemented in the following way for all $g\in G$:

\[\sum_{j}U_{ij}(g)A^j=\varphi(g)X(g)^{-1}A^iX(g)\,,\]Here, $U:G\rightarrow\text{GL}(\mathcal{H})$ is the representation on the physical level and $\varphi:G\rightarrow\text{U}(1)$ is a 1D representation of $G$. The matrices $X$ on the other hand do not necessarily form an ordinary representation. By the fundamental theorem of MPSs, they only need to form a projective representation as defined above (conform Wigner’s theorem).

The question now of course becomes how this is related to group cohomology. For this, we return to the defining equation of projective representations. Associativity of the group (homo)morphisms requires that

\[\omega(g_1g_2,g_3)+\omega(g_1,g_2) = \omega(g_1,g_2g_3)+\omega(g_2,g_3)\]up to an integer multiple of $2\pi$. Because projective representations are only defined up to a phase factor, $\omega(g,h)$ is equivalent to $\omega(g,h)+\varphi(gh)-\varphi(g)-\varphi(h)$ for any function $\varphi:G\rightarrow\text{U}(1)$. Looking back at the previous section, it can be seen that the difference between these two expressions is exactly a $1$-coboundary and, hence, projective representations are classified by the second cohomology group $H^2(G;\text{U}(1))$!

To complete the classification of SPT phases with on-site symmetry group $G$, we also have to take into account the representation $\varphi:G\rightarrow\text{U}(1)$. Again, by inspecting the definition of cohomology groups in the previous section, it should be clear that $H^1(G;\text{U}(1))$ is exactly the set of inequivalent classes of such representations. It follows that SPT phases in 1D systems are classified by the group $H^1(G;\text{U}(1))\times H^2(G;\text{U}(1))$.

In the previous section, we looked at translation-invariant systems with an on-site symmetry. However, on-site (internal) symmetries are not the only type of symmetries that are of relevance in physics. A very important type of symmetry that we did not cover are the spatial symmetries, e.g. rotations. Whereas the on-site symmetries determine the phase classification and the form of single-site MPS tensors, spatial symmetries will also determine how MPS tensors (of a general nonuniform MPS) on different sites are related.

A first important remark is that the spatial symmetry groups that we can consider in the case of lattice systems are, almost by definition, not the same as what we consider in our daily lives. Lattices in Euclidean space have finite symmetry groups. For example, whereas the plane $\mathbb{R}^2$ has as rotation group $\text{SO}(n)$, the square lattice has rotation group $\mathbb{Z}_4$. In three dimensions, there exist 230 distinct symmetry groups or, equivalently, 230 distinct lattices. In one dimension, however, the classification is a lot easier. Only two possibilities remain:

- An equidistant sequence of points, with a point at the origin.

- An equidistant sequence of points, with the origin in between two points. Since the classification is pretty boring in one proper dimension and since physical systems are essentially never truly one-dimensional, we move to a slightly more interesting setting.

- $T$: one-site translation,

- $H$: reflection across the horizontal axis,

- $V$: reflection across the vertical axis,

- $G$: glide reflection, i.e. translation by half a cell followed by $V$, and

- $R$: rotation over $\pi$ (equal to $HV$).

Although using frieze groups is already a step in the right direction, it is still not exactly what we want for the reason that, in the classification of frieze groups, the distinct sites are considered to be exactly the same (up to a spatial transformation). However, in physical systems, this is not necessarily the case. Instead of considering one-site translations, we will first fix a unit cell size $n\in\mathbb{N}$. A general transformation then has the affine form

\[A\vec{x} + \vec{\omega}\,,\]where $A=\begin{pmatrix}\pm1&0\\0&\pm1\end{pmatrix}$ and $\omega=\begin{pmatrix}k\\0\end{pmatrix}$ for $k\in\mathbb{Z}_n$. The closure property of groups implies that

\[\vec{\omega}_{gg'}=A_g\vec{\omega}_{g'}+\vec{\omega}_g\mod n\]or, since only the first component of the $\vec{\omega}$’s is nonzero,

\[\omega_{gg'} = \beta(g)\omega_{g'}+\omega_g\mod n\,,\]where $\beta(g)\in\{-1,1\}$ depending on the sign of the first component of $A$. Recalling the section on cohomology, this is exactly the $1$-cocycle condition with action $\beta$ and, hence, the symmetry actions will be characterized as elements in $H_\beta^1(G;\mathbb{Z}_n)$. For a symmetry group $G$ of order $N$, this gives a system of $N\times N$ equations and, hence, quickly becomes unmanageable. Before introducing an efficient algorithm for solving these equations, we will first consider a small example where $G=\mathbb{Z}_3$.

Consider a $\mathbb{Z}_3$ on-site symmetry group on a periodicity-3 lattice. When writing out the cocycle conditions and removing trivial terms/equations, we are left with the following system:

\[\begin{cases} \omega_2+\omega_3=0\,,\\ \omega_2+\omega_2=\omega_3\,,\\ \omega_3+\omega_3=\omega_2\,. \end{cases}\]Solving this system (over $\mathbb{Z}_3$) gives three distinct solutions. The trivial one, where $\omega_2=\omega_3=0$ and two nontrivial chiral solutions:

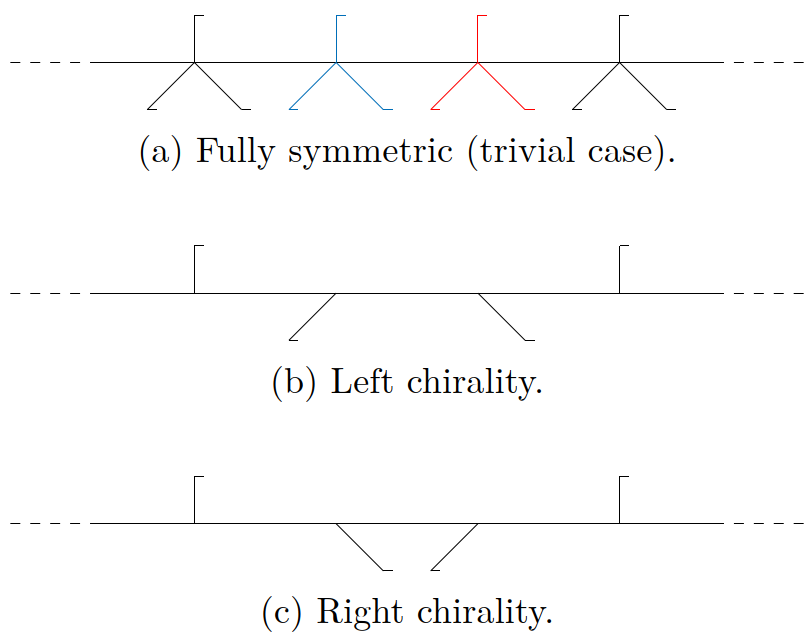

\[\begin{aligned} \omega_2=1&\qquad\omega_3=2\,,\\ \omega_2=2&\qquad\omega_3=1\,. \end{aligned}\]In the trivial solution, all sites are fully symmetric under $\mathbb{Z}_3$. However, for the chiral solutions, the different sites are related as can be seen in the figure below (the small horizontal lines at the tips are added to break reflection symmetry).

Although an explicit construction of MPS tensors for various examples of frieze groups is definitely interesting, we refer the interested reader to the references at the bottom of this post. We will, however, explain how to numerically solve the cocycle conditions using the Smith normal form. This algorithm is very similar to Gaussian elimination. Given a matrix $A$ with coefficients in a principal ideal domain $\mathfrak{P}$, the idea is to obtain a decomposition $U\Lambda V$ with $U,V$ invertible and

\[\Lambda=\left( \begin{array}{c|c} \mathrm{diag}(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_r)&0 \\ \hline 0&0\\ \end{array} \right)\,,\]where $r$ denotes the rank of the matrix and the coefficients $\{a_1,\ldots,a_r,\ldots\}\subset\mathfrak{P}$ satisfy that $a_i$ divides $a_{i+1}$ for all $i\leq r$. Since the rank of the matrix should not be altered as this is one of the important quantities when computing (co)homology, we must ensure that all operations in the algorithm leave the rank invariant. As in the Guassian elimination algorithm, these are the elementary row/column operations:

- Type I: Exchanging rows or columns.

- Type II: Multiplying a row or column by a nonzero number.

- Type III: Adding a multiple of a row/column to another row/column.

The algorithm proceeds iteratively. The procedure at every iteration goes as follows:

- We look for the smallest entry (in absolute value) and, by type-I moves, bring it to the upper left corner of the matrix. This entry will be called the pivot.

- By type-III moves, we try to set all entries below and to the right of the pivot to 0. If this is not possible, we reduce the magnitude of the entries below and to the right of the pivot and start anew (potentially changing the pivot) until the zero entries are obtained.

- Then, we check if the pivot divides all other entries. If so, we can proceed. If not, we use type-III moves to make the first entry that is not divisible by the pivot divisible and start anew until all entries are divisible by the pivot.

- After satisfying the divisibility condition, we check if the pivot is negative. If not, we use a type-II move (with factor $-1$) to make it positive.

The next iteration proceeds by working in the submatrix obtained by removing the first row and column.

In this section, some (arguably random) other applications of group cohomology are covered. I stumbled upon the first example whilst ‘casually’ scrolling on the $n$Lab, in particular, the page on causal perturbation theory.

Consider a group $G$ of would-be renormalization transformations. This group comes equipped with an action on the algebra of local observables of a perturbatively interacting QFT . This action also induces an action on $S$-matrix schemes4 (by conjugation). More generally, if we have a collection $\{\text{vac}_h\}_{h\in G}$ of free field vacua, indexed by the group $G$, the action of $G$ relates the different induced Wick algebras of local observables:

\[\mathrm{rg}_h(A\star_{h^{-1}h_0} B) = \mathrm{rg}_h(A)\star_{h_0}\mathrm{rg}_h(B)\,,\]where $\star_h$ denotes the Wick star product induced by the choice of vacuum state $\text{vac}_h$. Now, if $\{S_h\}_{h\in G}$ is a collection of $S$-matrix schemes around these vacua, the induced action on $S$-matrices

\[S_{h_0}^h = \mathrm{rg}_h\circ S_{h^{-1}h_0}\circ\mathrm{rg}_h^{-1}\]gives another $S$-matrix scheme around $\text{vac}_{h_0}$. For a fixed $h_0\in G$, the map $h\mapsto S_{h_0}^h$ is called the RG flow of $\text{vac}_{h_0}$. By the main (fundamental) theorem of causal perturbation theory (or perturbative renormalization theory), any two $S$-matrix schemes around the same vacuum are related by a vertex redefinition. It follows that

\[S_{h_0}^h = S_{h_0}\circ Z_{h_0}^h\]for a perturbative transformation $Z$ on the space of local observables. If the local observables, i.e. the interaction vertices, are thought of as being determined by the values of the coupling constants $\{g_i\}_{i\in\mathscr{I}}$ multiplying the terms in the interaction Lagrangian ($\mathcal{L}_{\text{int}}=\sum_{i\in\mathscr{I}}g_i\mathcal{L}_i$), then $G$ induces running coupling constants through $Z$:

\[Z_h: \{g_i\}_{i\in\mathscr{I}}\mapsto\{g_i(h)\}_{i\in\mathscr{I}}\,.\]Now, acting with two RG transformations $h,h’\in G$, gives:

\[\begin{aligned} S_{h_0}\circ Z_{h_0}^{hh'} &= S_{h_0}^{hh'}\\ &= \mathrm{rg}_{h}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h'}\circ S_{h'^{-1}h^{-1}h_0}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h'}^{-1}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}^{-1}\\ &= \mathrm{rg}_{h}\circ S_{h^{-1}h_0}^{h'}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}^{-1}\\ &= \mathrm{rg}_{h}\circ S_{h^{-1}h_0}\circ Z_{h^{-1}h_0}^{h'}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}^{-1}\\ &= \mathrm{rg}_{h}\circ S_{h^{-1}h_0}\circ\left(\mathrm{rg}_{h}^{-1}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}\right)\circ Z_{h^{-1}h_0}^{h'}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}^{-1}\\ &= S_{h_0}\circ Z_{h_0}^h\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}\circ Z_{h^{-1}h_0}^{h'}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}^{-1}\,. \end{aligned}\]Now, since the assignment of vertex redefinitions is injective, we obtain:

\[Z_{h_0}^{hh'} = Z_{h_0}^h\circ (\mathrm{rg}_{h}\circ Z_{h^{-1}h_0}^{h'}\circ\mathrm{rg}_{h}^{-1})\,.\]If we would work out the cocycle condition for $k=1$ in the section on cohomology, we would see that the equation above is exactly the (multiplicative version of5) the $1$-cocycle condition with respect to the adjoint action of $G$ on the Stückelberg–Petermann group of vertex redefinitions! When $G$ consists of scale transformations, as in the Wilsonian approach to renormalization, the cocycle is known as the Gell-Man–Low cocycle.

- Vancraeynest-De Cuiper, B., Bridgeman, J. C., Dewolf, N., Haegeman, J., & Verstraete, F. (2023). One-dimensional symmetric phases protected by frieze symmetries. Phys. Rev. B, 107(11):115123. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.107.115123

- Dewolf, N. (2019). Ruimtelijke Symmetrieën en Symmetriebreking met Matrix Product Toestanden. Universiteit Gent. https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:002782900

(Note: An updated Arxiv version will appear as soon as I have updated the manuscript.) - Haegeman, J., & Verstraete, F. (2017). Diagonalizing transfer matrices and matrix product operators: A medley of exact and computational methods. Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics, 8(1):355–406. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031016-025507

- X. Chen, Z.-C. Gu, Z.-X. Liu, & X.-G. Wen. (2013). Symmetry protected topological orders and the group cohomology of their symmetry group. Phys. Rev. B, 87(15):155114. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.155114

-

To be entirely correct, we should be working with its projectivization $\mathbb{C}P^2$. ↩

-

These systems are governed by a local, gapped Hamiltonian. Gapped means that, even in the thermodynamic limit, there exists an energy gap between the ground state and the first excited state. ↩

-

This will be proven in the next section. ↩

-

The function that maps interactions to time-ordered exponentials. ↩

-

The nonabelian version of group cohomology is a special theory. Using the ordinary definition of $k$-cocycles, where ‘addition’ is replaced by the nonabelian product on $A$, only leads to a well-defined theory for $k\in\{0,1\}$. The reason for this is that the more abstract definition through homotopy theory requires the construction of so-called deloopings. By the Eckmann–Hilton argument, these only exist for nonabelian groups. ↩